Feeling

Náttúran er það fyrsta sem

tekur á móti þegar komið er inn í dalinn og gróðurinn er allsráðandi til allra

átta. Dalurinn er því eins og vin í eyðimörkinni, griðastaður fyrir langþreytta

malbiksbúa sem þrá augnabliksstund í amstri dagsins umvafðir gróðri og náttúru.

Við nánari athugun er þó ekki allt sem sýnist. Ef rýnt er í gróðurinn er hér á

ferð erkióvinur malbiksbúans, illgresi. En hvað gerir illgresi að

illgresi og afhverju er það frábrugðið öðrum skrúðgróðri? Fyrir náttúrunni hefur allur

gróður jafnt vægi en um leið og maðurinn nálgast með sína lífshætti og

mannvirki breytast skilgreiningarnar og ákveðinn gróður verður æðri öðrum.

En hver er þá í raun illgresið, gróðurinn sem spillir borginni eða maðurinn sem spillir náttúrunni?

En hver er þá í raun illgresið, gróðurinn sem spillir borginni eða maðurinn sem spillir náttúrunni?

The first thing capturing the

attention when arriving at the valley is vegetation. It is like an oasis in the desert, sanctuary for the tired pavement people who yearn

for a moment around greenery and plants from their daily routine. However, not

everything is as it seems at first. Up on a closer inspection the greenery in question

is the worst enemy of the citizen, weed. But why is weed different from

other vegetation? Every plant is equal to nature

but as soon as nature gets closer to man and the manmade certain plants become superior

to others.

Who is then the real weed, is it the greenery that destroys the city or man that destroys nature?

Who is then the real weed, is it the greenery that destroys the city or man that destroys nature?

The steps to good architecture

From the beginning, the history of architecture has been intertwined with the history of mankind. During the struggle for life and death, architecture was intended to provide shelter but began to evolve into something greater and more substantial. In line with the emphasis of our immediate environment changing and the development of mankind, the components of good architecture have increased. The oldest known written text on good architecture is De architectura by the Roman architect Vitruvius. In his view, there are three basic laws of the field, durability, utility, and beauty. Albeit, the principles of Vitruvius’ words are still relevant to this day concerning the construction of structures, the laws may have expanded beyond their original meaning with competency and experience. However, new challenges surface that call for new solutions in designs and even further broaden the requirements of good architecture. Narrowing down what these characteristics consist of is getting increasingly more difficult, it becomes clear that architecture has always been about much more than just shelter.

The necessity for durability in architecture has been vital knowledge since its beginning. If the house crumbled it could not provide any shelter. With perseverance, mankind was able to develop methods that overcome gravity to make the impossible possible, culminating in buildings such as the Egyptian pyramid or the Roman arc. Still to this day, people are working on inventing the wheel, solving problems, and inventing new and better methods to overcome obstacles. As an architect, it is crucial to understand these methods and apply them accordingly. Otherwise, a building that is poorly made, and does not meet the demands of gravity, weather or wind, cannot be enjoyed to its full extent. Durability also ensures that the building withstands the tests of time and does not become obsolete as soon as the paint dries. Therefore, it is important to not only choose durable but as well materials that are known to hold their own against the popular fashion trends of a modern household. A prominent problem in a fast-paced society is the speed of construction and frugality that follows, which often results in good buildings being compromised. Looking at the whole, it would be more economical to do better from the start instead of having to take care of maintenance or even demolishing and rebuilding.

Structures being well built is just the first step towards good architecture but Vitruvius considered utility just as important. If a building has no purpose then what is it for? Good architecture must serve its purpose and be useful to its user. Thus, it is necessary to always be in alignment with them during the design process. Structures must also be able to contribute something to the community, serve it as a whole, and exist with the purpose of being considered good.

„Good architecture tells us something about the world. It tells us something about history, about culture, about how the society works and finally, it tells us who we are. And good architecture, or art in general, enables us to live a more dignified life than we could without art.”

Until now, what has represented much architecture is that only a certain elite can enjoy what Pallasmaa describes. It seems that people with reduced mobility are regularly forgotten in the design but a good building can hardly be considered good if it only welcomes a selection of people. Accessibility has recently been recognized as both usefulness and necessity. The Housing and Construction Authority in Iceland has made a requirement about Universal design. “With requirements for universal design according to paragraph 1, relevant buildings specified therein shall be designed so that they are useful to everyone, all can travel around them and function without special assistance, cf. further requirements of this type of regulation.” Communities can expect a tremendous amount of work to correct the misunderstanding that buildings are not for all.

The third and last characteristic of good architecture according to the Roman was beauty but that characteristic has been heavily debated throughout history. Many want to argue that a good building does not need to be beautiful if it is still standing and serves its purpose. That the word veritably is superficial and does not belong alongside a description of good architecture. Looking at beauty from the standpoint of phenomenological perspective it is relative and can therefore become tricky to design a building that is beautiful for all. For Vitruvius beauty consisted of proportion, scale, the way light lingered, form, and rhythm. However, the word beauty applies to more than what the eye can behold, which is periodically forgotten in discourse.

Architect and scholar Juhani Pallasmaa’s life work has been driven towards working against the visuals of modernism and to show that architecture is not exclusively experienced with one sense. The beauty of good architecture belongs in the experience, felt with all our combined senses and the emotion the building invokes. A building that reflects emotions back and conjures sentiments, becomes both beautiful and special. This experience is reminiscent of the child’s world, which grasps its surrounding in a different way and uses more senses than the adult. A child being asked about good architecture will choose a building they grew up in, how they perceived touching, hearing, seeing, smelling, and tasting their home in many different ways. This building lives with individuals throughout adolescence and follows them into adult life, being the most beautiful to them despite the cohesive design of the building. Thus, it is important that good architecture influences all senses; to deepen the experiences of the user and awaken the inner child.

It is not only the meshing of senses that is essential to good architecture, but the meshing of all there is. Grandeur is instinctual to man, but many want to become the greatest and grandest in everything they undertake. When such thinking controls actions, it becomes easier to get off track because architecture does not revolve around creating a single work that excels above all but its purpose is to blend into its surroundings seamlessly and service its surroundings.

“The presence of certain buildings has something secret about it. They seem simply to be there. We do not pay any special attention to them. And yet it is virtually impossible to imagine the place where they stand without them. These buildings appear to be anchored firmly in the ground. They make the impression of being a self-evident part of their surroundings and they seem to be saying: “I am as you see me and I belong here”.

A building does not stand isolated and should not be designed as such. It is important to design it in relation to its nearest surroundings and in according to cultural history. In actuality, the exterior walls of buildings are nothing more than the interior walls of a city that consist of streets and squares. Thus must the whole, community property of all its inhabitants, serve the whole community. Hence, if designed with this in mind, the whole automatically becomes closer to its authentic self, more attractive, and therefore safer. Safety is a sought-after feeling and if it is not present evading the situation becomes a priority. The interior city walls transform into some kind of defense for its inhabitants, similar to the Roman battlements. Safety must not be forgotten in the discourse about good architecture.

In modern society, many experience themself as unsafe concerning the discussion about the security of the future. In their greatness, man has managed to compromise themselves, the earth, and its future, and create new problems for the coming generations. Mankind’s consumption habits have made sure that the gifts received from the earth are running out, and it’s only recently been realized that they are transient. The damage has been done but there is still time to try to save the world from ruin. By reducing consumption and reevaluating the lifestyle, it is possible to combat more damage that will be done. What do architects face in such a world, working with a practice that is addicted to consumerism, illusions of grandeur, and the need for construction in a world that is actively restricting?

With this in mind, the first of Vitruvius’ characteristics, permanency becomes even more crucial regarding good architecture nowadays. From now on, each step must be rational and thought out. No longer is it acceptable to build for the sake of building, and no longer is it tolerable to repeat the same mistakes. Now, the reasons for constructing have to contain purpose and must focus on development, and the reusable. For years demolition has been an influential part of construction trends that did not qualify as good architecture, did not pass architectural standards, or was simply built too quick to stand the effects of its surroundings. Demolition is a costly process whereas a substantial amount of materials spoil. Unnecessary energy is wasted to use new materials and even more energy. By using the energy and the structure that is already available, and thus materials and power are conserved reducing waste. This way, the lifetime of the building extends, and has the potential to become good architecture.

When constructing from the beginning it is important to include sustainability and try to avoid spending unnecessary energy. Sustainable architecture “refers to design that creates healthy living environments while aiming to minimize negative environmental impacts, energy consumption and use of human resources.” Each nation has acquired its own energy resources, but history has shown that some find their own resources not enough and have dipped their fingers into other nations’ resources as if what they had was simply not good enough. With the use of localized materials, waste can be drastically reduced and lessen the nation’s carbon footprint. It becomes quite ironic how much energy was spent in tearing down the turf houses that were resourced from local materials; fully sustainable.

Clearly, architecture as a profession will not cease with sustainability. The solutions are readily available, but they must be sought out with determination. New goals must be set, as well as changing the mindset as a whole. Learning to design not only for the building but for man and the environment is crucial. Good architecture must be a requirement, not a choice. To build and then demolish must be no longer acceptable. If each architect is mindful in their design, every building becomes good and if every building is good then spaces become better, more open, and much more accessible. Which in turn enhances the all-around beauty of its environment and increases the quality standard of life.

Good architecture can be hard to define as the characteristics are many and complicated to the extent that none of them can stand alone. The problem is that the definition is ever-changing and constantly adding on more characteristics as experience grows. The phenomenon is relative, what constitutes good architecture to one person could be the opposite for another. In principle, however, it is a combination of all that is technical, emotional, and natural, providing humanity with security, well-being, and respecting its environment and the earth. If the phenomenon is simplified, ten steps could be taken into account, even though the list is not exhaustive. Good architecture must be durable, well-made, and user-friendly. It has to serve the community, be accessible, awaken senses and work in context with its environment, provide security and sustainability. All this has to be in harmony: “the quality of the finished object is determined by the quality of the joins.” After all, good architecture is not really about the building itself. Good architecture revolves around mankind, emotions, and our surroundings.

Heimildaskrá

Anna María Bogadóttir. „Borg er miklu meira en samansafn bygginga: viðtal við Jórunni Ragnarsdóttur hjá Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei.“ HA, íslensk hönnun og arkitektúr, vor 2018, 54-65.

Barker associates. „Sustainable architecture: What is it and how do we achieve it?.“ Barker associates. Sótt 18. október af https://www.barker-associates.co.uk/service/architecture/what-is-sustainable-architecture.

Betsky, Aaron. „What it means to make good architecture.“ Architect, 6. febrúar 2015. Sótt 17. október af https://www.architectmagazine.com/design/what-it-means-to-make-good-architecture_o.

„Byggingarreglugerð.“ Mannvirkjastofnun. Sótt 17. októberber 2021 af

http://www.mannvirkjastofnun.is/library/Skrar/Byggingarsvid/Leidbeiningarblod/6.1.3%20%20%20Kr%C3%B6fur%20um%20algilda%20h%C3%B6nnun-1.2.pdf.

Gombrich, E. H. Saga listarinnar. Halldór Björn Runólfsson þýddi. Reykjavík: Opna, 2008.

Jacobs, Jane. The death and life of great American cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

Klein, Naomi. This changes everything: capitalism vs. the climate. New York: Simon Schuster, 2014.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. „Juhani Pallasmaa Interview: Art and Architecture.“ Myndband, 4:40. Sótt 15. október 2021 á https://vimeo.com/270345281.

Pallasmaa, Juhani. The eyes of the skin. Chichester: Willey-Academy, 2005.

Vitruvius. The ten books on architecture. Morris Hicky Morgan þýddi. New York: Dover Publications, 1960.

Zahavi, Dan. Fyrirbærafræði. Björn Þorsteinsson þýddi. Reykjavík: Heimspekistofnun Háskóla Íslands, 2008.

Zumthor, Peter. Thinking architecture. Basel: Birkhauser, 1998.

Of Horse and Man

Hanna Lind Rosenkjær Sigurjónsdóttir

Katrín Dögg Óðinsdóttir Kaewmee

Verkefnið „af hestum og mönnum“ fjallar um jafnvægi í samskiptum þessara tveggja dýra. Íslenski hesturinn hefur fylgt hinum íslenska manni frá örófi alda og er fyrir löngu orðinn stolt okkar og prýði. Auk þess er hann stór hluti af efnahagskerfi okkar sem ein helsta útflutningsvara þjóðarinnar og aðdráttarafl í túrisma. Tæplega 10.000 hestar eru á Íslandi og þurfa þeir allir að eiga í samskiptum við manninn að einhverju leyti.

Samskipti þessara tveggja tegunda geta þó reynst flókin. Samkvæmt lögum náttúrunnar er maðurinn rándýrið og hesturinn bráðin. Sem bráð er hestinum því lífræðilega lært að vera hræddur við manninn og ef ekki er farið rétt að í samskiptum getur sú hræðsla orðið yfirráðandi í lífi hestsins. Erfitt getur verið að greina hræðsluna en hún getur haft gífurleg áhrif á andlega og líkamlega heilsu dýrsins. Að sama skapi er þekkt einkenni meðal manna að vera hræddur við hesta enda stórar og stæðilegar skepnur. Því er mikilvægt að jafnvægi ríki í samskiptum þessara tveggja landnámsmanna Íslands og þeir umgangist hvor annan af væntumþykju og virðingu.

Ísland hefur lengi trónað á toppnum er kemur að velferð hesta. Nú hafa nýjar rannsóknir á vegum Animal Welfare Foundation hins vegar leitt í ljós að ekki er allt sem sýnist og hefur Ísland verið sakað um brot á dýravelferðarlögum vegna slæmrar meðferðar á blóðmerum. Blóðtökurnar sem um ræðir valda merinni mikilli vanlíðan og oftar en ekki varalegum skaða bæði líkamlega og andlega. Hafa þessar fréttir sett svartan blett á allt hestahald á landinu þó að hér komi í raun einungis fáir aðilar við sögu. Því er enn mikilvægara en áður að huga að velferð þessara skepna og standa vörð um þeirra heilsu og líðan.

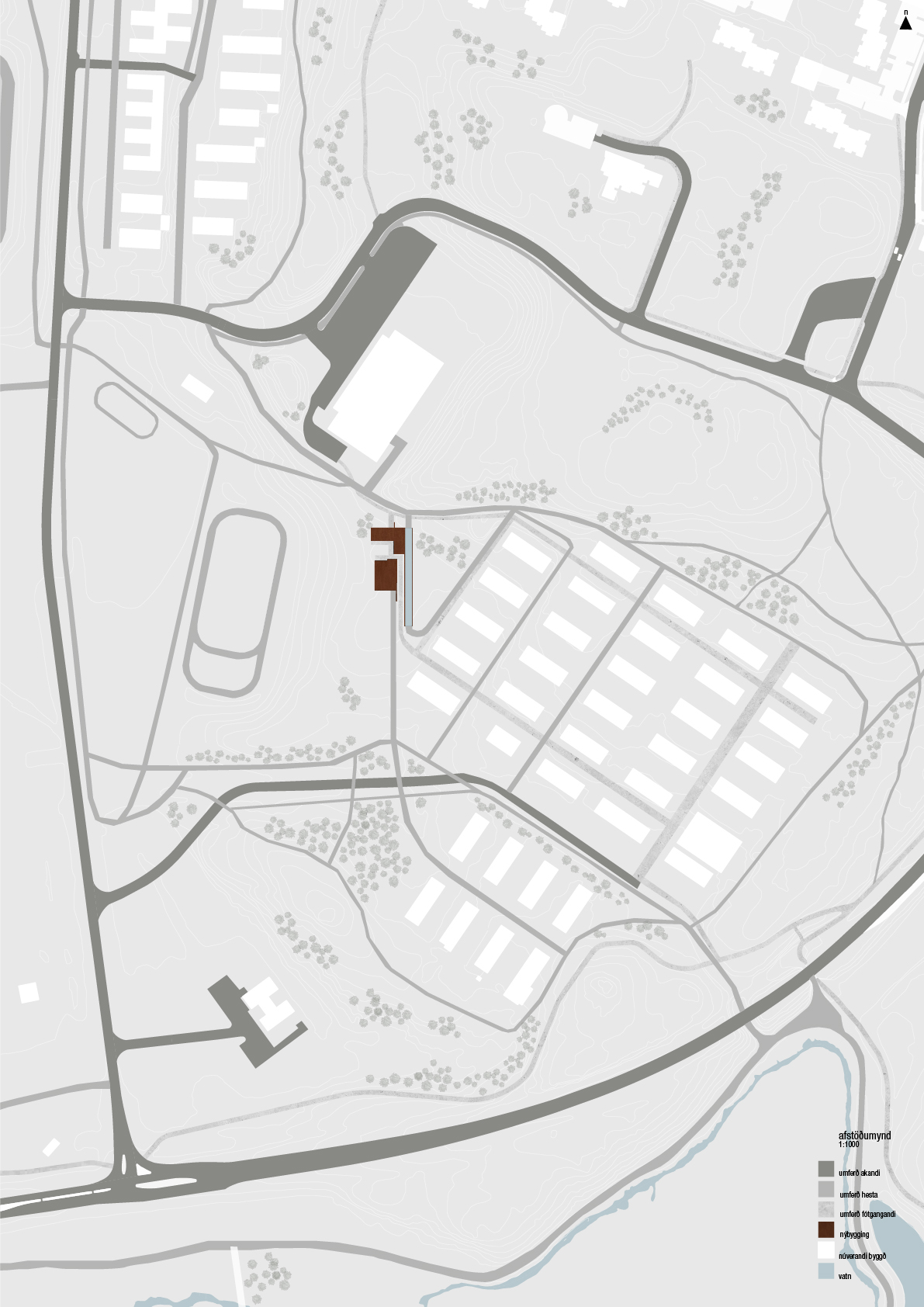

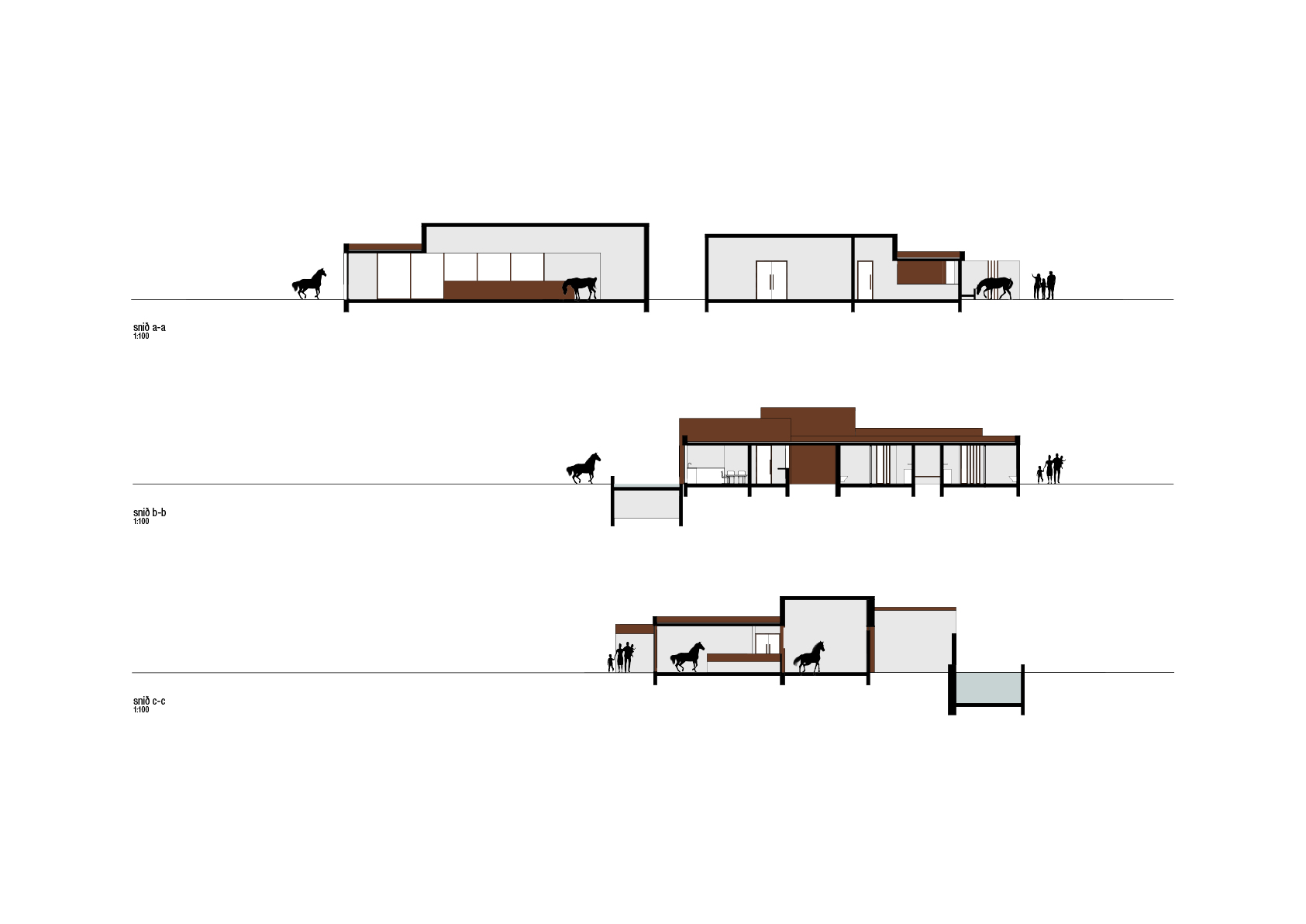

„Af hestum og mönnum“ er verkefni ætlað að koma í veg fyrir að nokkuð þessu líkt gerist aftur með því að brúa bilið á milli þessara tveggja dýra, með fræðslu og umgengniskennslu. Með samspili og jafnvægi milli hests og manns verður verkefnið til í formi þriggja massa í þungamiðju hestamennskunnar á höfuðborgarsvæðinu, Víðidal. Eru massarnir staðsettir miðja vegu milli reiðhallar og yngra hesthúsahverfis, með útsýni yfir einn af reiðvöllum svæðisins.

Reiðstígar og hestagerði umvefja bygginguna og fær hesturinn því að fylgjast með manninum og maðurinn hestinum þar til þeir mætast í kennslurými. Geta þeir þar fengið leiðsögn um þarfir hvors annars og aðstoð við að kynnast hvor öðrum betur svo að jafnvægi og traust ríki ávalt í samskiptum. Á svæðinu er einnig sýningarsalur þar sem maðurinn getur fræðst betur um hestinn og hans þarfir áður en hann tekur lokaskrefið í áttina að honum. Önnur aðstaða ætluð manninum á svæðinu eru salerni, móttaka og starfsmannaaðstaða. Rými hestsins eru túnin allt í kring og hestalaugin sem ætluð er til að bæta bæði líkamlega og andlega heilsu hestsins.

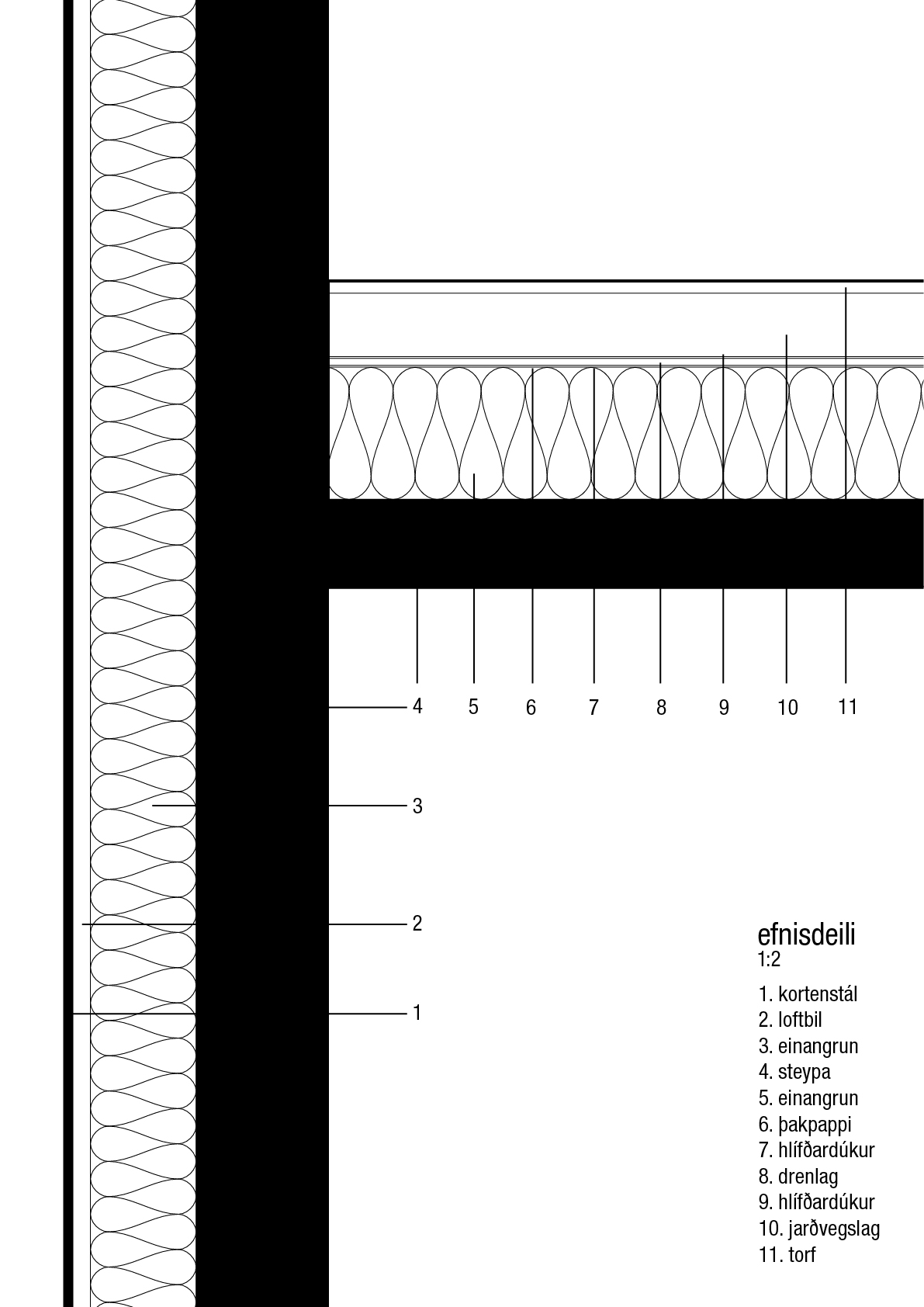

Efni byggingarinnar eru einnig valin með velferð hestsins í huga en rannsóknir sýna að náttúrulegir litatónar henta hans líðan best og valda sem minnstu áreiti. Því leituðum við í náttúruna á svæðinu en öll efnin og litina má nú þegar finna í einhverri mynd í Víðidalnum. Byggingin sjálf hlýtur þó ekki stífustu lögum náttúrunnar og er augljóslega mannsins verk. Jafnvægið sem ríkir víða í Elliðaárdalnum milli mannvirkja og náttúru verður þó til með tíð og tíma er veðrun, vindar og gróður fá að leika lausum hala um bygginguna og þannig gera hana á einhvern hátt að órjúfanlegum hluta af svæðinu.

Efni byggingarinnar eru einnig valin með velferð hestsins í huga en rannsóknir sýna að náttúrulegir litatónar henta hans líðan best og valda sem minnstu áreiti. Því leituðum við í náttúruna á svæðinu en öll efnin og litina má nú þegar finna í einhverri mynd í Víðidalnum. Byggingin sjálf hlýtur þó ekki stífustu lögum náttúrunnar og er augljóslega mannsins verk. Jafnvægið sem ríkir víða í Elliðaárdalnum milli mannvirkja og náttúru verður þó til með tíð og tíma er veðrun, vindar og gróður fá að leika lausum hala um bygginguna og þannig gera hana á einhvern hátt að órjúfanlegum hluta af svæðinu.

Urban Lab - Design Agency